Infiltrating IMSA – Sending the 962 stateside

In the early 1980s, Norbert Singer and his team penned a design which transcended sports car racing for almost fifteen years. Ditching their beloved tube frame chassis, Porsche’s first monocoque race car boasted three times the downforce of the all-conquering 917. Built to replace the ageing 936, the Porsche 956 was Singer’s answer to the conundrum of the upcoming Group C regulations for world championship sports car racing.

Utilising revolutionary ground effect aerodynamic technology, the Porsche 956 pulverised the competition. A debut win at Le Mans in 1982 kicked off a four-year streak of victories for the 956 at the world’s most important endurance race. Aside from utter dominance at Le Mans, the 956’s success spread across Europe. Most memorably, on the 28th of May 1983, an otherworldly display of bravery and technological prowess transported Stefan Bellof and the Porsche 956 into Nurburgring Nordschleife folklore. A lap of 6 minutes and 11 seconds commands much more than a mere footnote in Porsche’s Group C racer.

While the Porsche 956 swept all before it in Europe, competitors in the booming IMSA championship in North America plodded on with ever more extravagant modifications of the now outdated Porsche 935. Although Porsche’s customer racing department offered the 956 for sale to private entrants, why hadn’t this ground-breaking new machine made it across the Atlantic? In short – politics.

During the summer of 1980, a relationship between IMSA’s John and Peg Bishop and Alain Bertaut of the Automobile Club De L’Ouest (ACO) continued to blossom. As the promoters of the world’s top endurance events like Daytona, Sebring and Le Mans, co-operation rather than competition was key.

Bertaut and the Bishop’s shared similar values. Both believed in giving private entrants a chance to win by controlling costs. Keeping spectator entertainment value was also a priority. On a cross country trip across the USA in the Bishop’s motorhome, a blueprint for global sports prototype competition was drawn up. Keen to avoid the dominance enjoyed by the Porsche 935 at the time, Bertaut and the Bishop’s devised a simple and cost-effective formula where an entrant could potential buy an off the shelf chassis and fit an engine of their choice. This concept quickly became reality when IMSA announced, with the ACO’s support, the GTP regulations. Therefore, a common set of rules were ready to be implemented in North America and Europe.

However, politics soon intervened. While Alain Bertaut and the Bishop family had toiled to create a sustainable platform for global sports prototype racing, the powers that be within FISA had other ideas. Whilst consulting with several European manufacturers, many of whom never turned up to compete, FISA conjured an alternative ruleset called Group C.

Group C’s ethos was more open than the cost sensitive GTP rules devised in the United States. Furthermore, Group C would be governed by a limited amount of fuel per competitor. Unsurprisingly, the entertainment conscious Americans knew their fans would never turn up to watch the best drivers in the world coasting around to conserve fuel. Therefore, Group C wouldn’t fit IMSA’s requirements.

Not for the last time, politics split the global sports car community into two separate factions. Despite his best efforts to convince FISA of the virtues of the GTP ruleset devised on his road trip across the USA, Bertaut met a stiff wall of autocratic stubbornness.

Those who have watched Manish Pandey’s excellent ‘Senna’ documentary, may remember a scowling, bespectacled Frenchman who Senna clashed with frequently in driver briefings. Around a decade before, Jean-Marie Balestre, ignited similar hostility in the sports car world.

Keen to force through FISA’s Group C rules and satisfy his political allies, Balestre insisted that the ACO (the organisers of the Le Mans 24 hours) adopt Group C rules and shun the deal with IMSA. When Bertaut protested, Balestre responded with an icy threat of striking the 24 hours of Le Mans off the international calendar. An unthinkable proposition. Bertaut had been strong armed by the bullying Balestre.

Although America’s GTP and Europe’s Group C classes were similar, some fundamental differences created a barrier for Porsche’s new 956 Group C car to compete on US soil in IMSA competition. Porsche and IMSA met on the morning of the 14th of December 1981 to discuss a solution.

For Porsche, the answer seemed simple. IMSA could adopt the Group C rules. As previously mentioned, this was a nonstarter for the Americans. However, Jon and Peg Bishop had their own answer this technical conundrum.

To maximise a machine like the Porsche 956 for Group C competition, the driver had to be mounted far forward. In fact, the driver’s feet rested in the nose of the car. On the grounds of safety, this was a deal breaker for IMSA. Furthermore, the 956 used a pure-bred race engine, developed from the old 936. Again, such exotic powertrains didn’t fit with IMSA’s mantra of reducing costs and allowing privateers to compete.

In the end, negotiations stuttered to a stalemate, with neither party budging on their requirements. For the 1982 and 1983 seasons, Porsche’s game changing 956 prototype wouldn’t race stateside.

Porsche’s technical mastermind of the time, Norbert Singer, isn’t a man who takes no for an answer. Weissach’s engineering wizard deals not in problems, only solutions. Singer’s answer to the stateside equation, was the Porsche 962.

Addressing IMSA’s two non-negotiable demands, Singer increased the 956’s wheelbase to accommodate the driver and fitted a more production focused engine. By 1984, the new Porsche 962 was ready to cross the Atlantic for IMSA competition.

Porsche chose a happy hunting ground to debut their now IMSA friendly prototype. On arrival to Daytona International Speedway in 1984 for the annual 24-hour race, the German marque had won thirteen of the seventeen editions of the endurance classic. On such a crucial debut, Porsche left nothing to chance when selecting their drivers.

Only American racing royalty would do for the 962’s maiden voyage. Father and son team, Mario and Michael Andretti, received the call from Weissach to pilot an unliveried 962. Amongst enormous hysteria in Daytona’s vast pitlane, Mario Andretti climbed into the 962’s dome shaped cockpit to run in anger for the first time. Without any fuss whatsoever, the 1978 F1 World Champion immediately pushed to the limit, carving through traffic with surgical precision and apparent ease. Andretti qualified on pole in style, outpacing the Kreepy Krauly March 83G by a full two seconds and Jaguar’s XJR-5 by three seconds.

Unfortunately, dreams of a debut win for the 962 ended in retirement after only 127 laps of the Floridian circuit. Porsche retreated to Germany with 962-001 and retired the car from competition. However, the die had been cast for bountiful success in North America.

Two months later, the first Porsche 962s began arriving with eager customers. By virtue of paying their bill first, Bruce Leven’s Bayside Disposal team took delivery of 962-101. Bob Akin and Al Holbert soon received 962-102 and 962-103, respectively. By June, the 962 scored its first victory on American soil when Derek Bell and Al Holbert borrowed Leven’s car to win at Mid-Ohio. More wins followed at Watkins Glen, Road America, Pocono and Daytona. Although the IMSA title would go to Randy Lanier and his Blue Thunder March squad, the Porsche 962 had arrived.

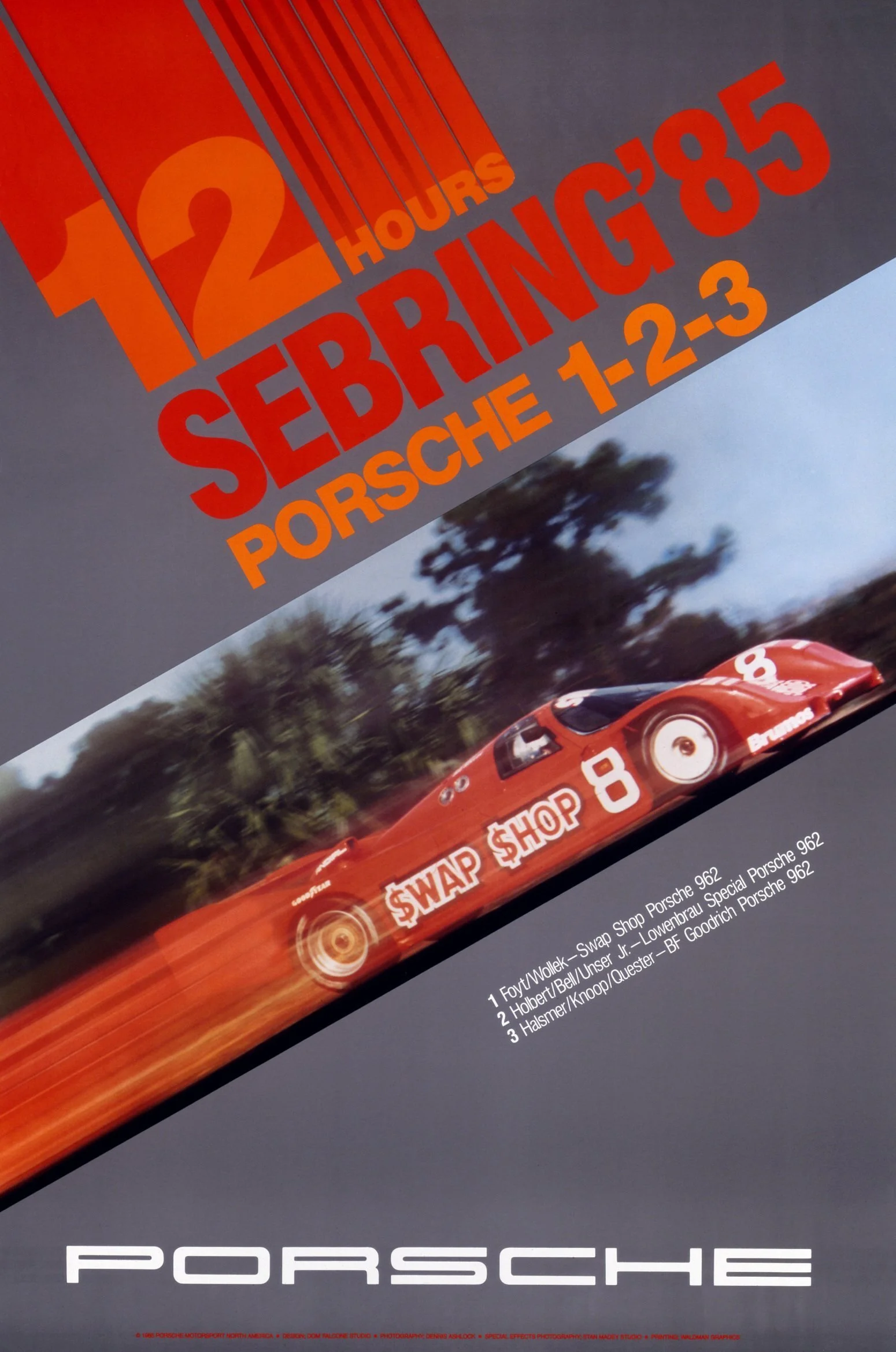

Powered by a band of loyal customer teams, Porsche dominated the 1985 season with 16 wins from 17 races. In the hands of Holbert, Akin, Leven, Dyson and many more, the 962 was now the gold standard. Furthermore, the car could be purchased from Weissach and even started with the turn of a key!

Five Daytona 24-hour wins, and four Sebring 12-hour triumphs complimented the 962s success at Le Mans in 1986 and 1987. However, without the car’s bountiful success and presence in North America, the 962 would not be the iconic car it is today.

Even after production concluded in 1991, the 962 continued winning for another three years. By 1994, the flame had finally begun to flicker to an ember after 12 years at the top. However, Norbert Singer had one last ace to play with his career defining masterpiece. Check back into Porschesport.com on the 2nd of July to discover the story of Singer’s final act with the 962.