Conceiving the unstoppable

Since Porsche’s ambitious debut at the 24 hours of Le Mans in 1951, the sports car firm has accumulated an unparralled tally of victories. To date, Porsche has scored 19 outright wins and 108 in class at the iconic race. No other manufacturer comes close.

Although Porsche immediately began winning in the smaller capacity classes with various iterations of the 356, 550 and 718, outright victory at Le Mans seemed a distant and ludicrous fantasy.

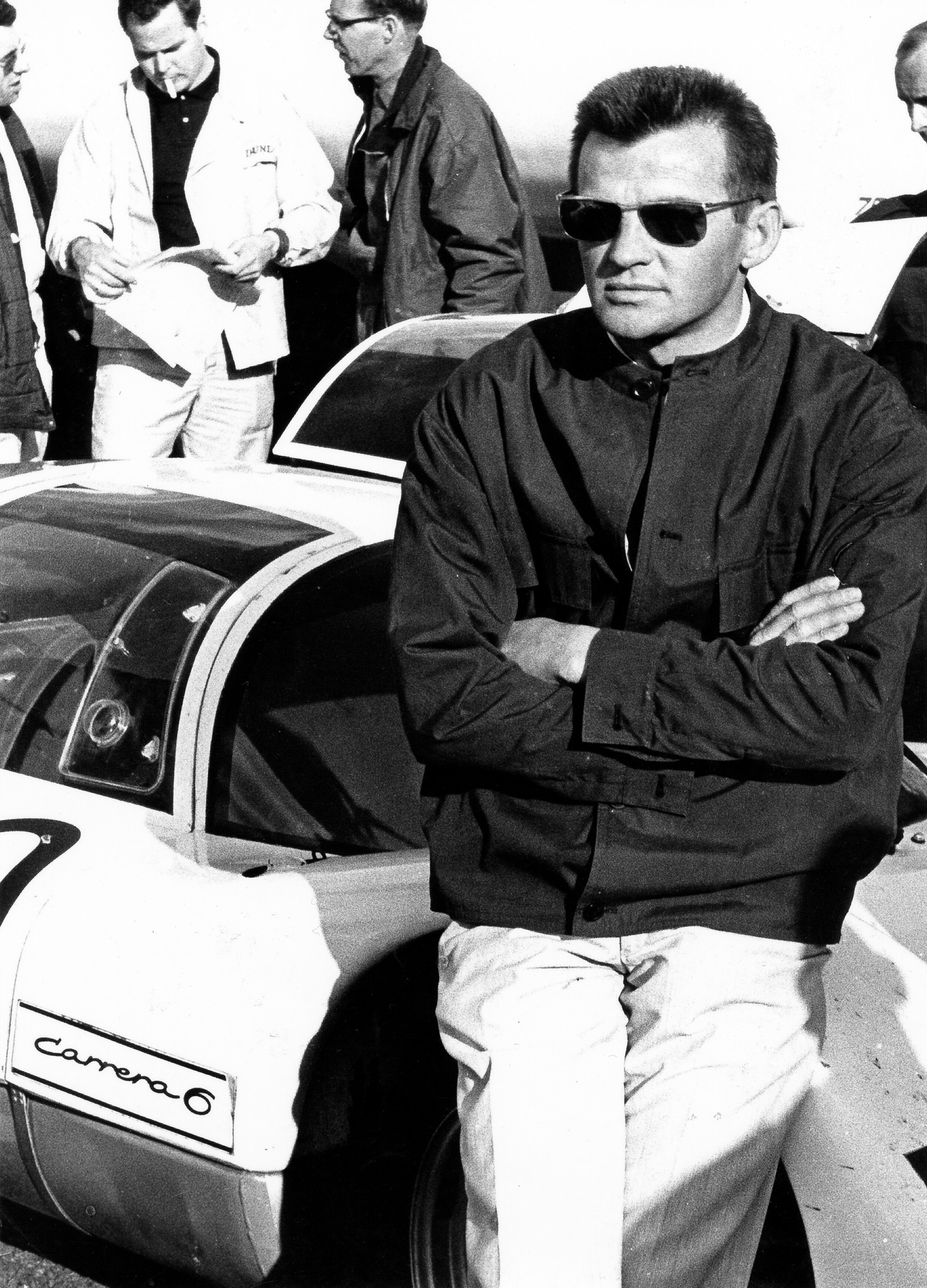

For the first quarter century of Porsche’s existence, the company was owned and run by the Porsche family. In 1965, an enthusiastic and determined family member took charge of the company’s motorsport efforts. Grandson of Dr Ferdinand Porsche and son of Louise Piech (nee Porsche), Ferdinand Piech had grand plans for the family firm.

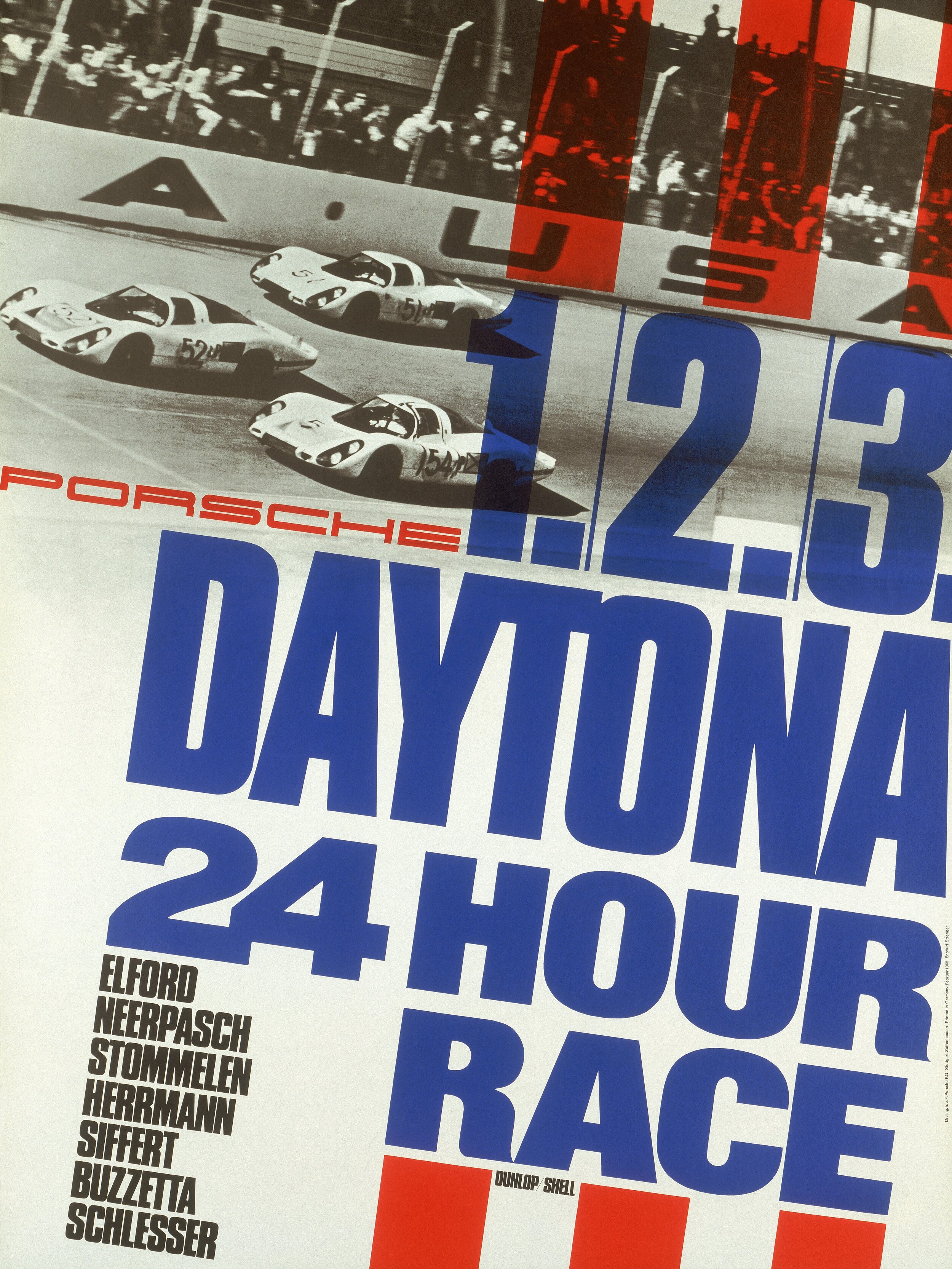

Piech was fed up with Porsche being known as the underdog, even though the Stuttgart brand continued to overachieve. Despite being a relatively young man, Piech ruthlessly chased an ambition to win the great endurance classics overall. Utilising the 907 prototype, Porsche’s elite factory drivers triumphed at the 1968 Daytona 24 hours and Sebring 12 hours. However, the grandest prize at Le Mans eluded Piech and the Porsche team.

At the 1967 24 hours of Le Mans, a bizarre tale of politics and controversy laid the foundations for Porsche to build the greatest racing car of all time. Under pressure from the seismic force of Ferrari and the Automobile Club de l’Ouest, the governing body of the world championship for sports cars (C.S.I) decided to limit sports prototypes engines to 3 litre capacity. Thus, chasing out the dominant Ford GT’s and similar American cars with large capacity engines.

Apparently implemented based upon safety concerns, the rule change was regarded as a blatant attempt to flush out muscular American entries from the 24 hours of Le Mans and the World Championship. Furthermore, manufacturers were given a paltry 6 months’ notice to prepare new machines for the 1968 season. This dictatorial decision was met with deafening outrage throughout the sport. American delegates from Daytona and Sebring called out for a “more democratic approach.” Nevertheless, like many autocratic rulings, the decision was final.

It is hard to determine what angered the manufacturers and stakeholders more, the rule change itself or the way the new regulations were arrogantly forced through without consultation.

Following the significant uproar, a small consolation was eventually made. Thus, exposing a vital loophole. If twenty-five examples could be built and offered for sale, then a 5-litre prototype could compete. No one within the sports governing powers had the foresight to believe any constructor would attempt to build a car to these rules.

News of this slight retreat sent the Porsche family to the boardroom to revise their racing plans. They emerged having signed off the project which eventually produced Porsche’s greatest competition machine – the 917.

With the company destined to be publicly listed on the orders of Ferdinand Piech a few years later, the 917 would be the last competition machine to be signed off exclusively by the family. Only under the autonomy of family reign could such a decadent pursuit of racing glory be considered by a company of Porsche’s means.

Porsche had ten months to design, develop and build twenty-five prototype racing cars. An inconceivable timeframe in a contemporary context. Although Porsche were still a relatively small concern, those working at Zuffenhausen had vigorous ambition. No more so than Ferdinand Piech.

A family connection to the VW Beetle proved critical to raising the colossal finance required for the 917 project. Keen to prolong the life of the Beetle and it’s air-cooled powertrain, Volkswagen provided funds to develop the 917’s engine which would also be air-cooled. Without this investment from VW, the 917 may have remained on the drawing board.

Ferdinand Piech was betting large on the 917. Developing the 917 eventually cost a reported DM 20,000,000. Le Mans victories and world championships were compulsory. Failure was unthinkable.

To develop such a sophisticated machine on an exceptionally tight timeline, Porsche relied on the loyalty of their band of engineering brains and their mighty work ethic. Arguably, the 917’s engine was the toughest problem to solve. This task fell to Hans Mezger and his team.

A graduate of Stuttgart technical institute, Mezger had worked exclusively for Porsche throughout his career. Lighting cigarette after cigarette, Mezger worked long into the evenings pondering Porsche’s all or nothing prototype motor. The 917’s engine would be an enormous step up from anything ever to leave the Zuffenhausen works.

Despite his team’s valid concerns regarding timeframe, Mezger understood the magnitude of the opportunity with the 917. Mezger convinced his team that the 917 project was the best chance to achieve the greatest honour in endurance racing. Not known for slacking in the first place, the whole of the Porsche works rallied together and showed unseen levels of commitment in pursuit of their ultimate racing car.

Eventually, Mezger used the existing three-litre, 8-cylinder motor from the 908 as a starting point. When Mezger and his band of engineers emerged from the top-secret skunkworks, the world’s largest air-cooled race car engine was ready to be tested for the first time. This 4.5 litre masterpiece immediately produced 540 horsepower and would soon be generating even more grunt.

So vast was the 917’s engine that the cooling fan gulped 2400 litres of air per second at maximum revs. This 12-cylinder powerhouse was ready to propel Porsche to the top step at the 24 hours of Le Mans.

Chassis and suspension guru, Helmut Flegl, was tasked with creating a home for Mezger’s sledgehammer motor. Much like Mezger, Flegl worked tirelessly to find solutions for the 917’s chassis, bodywork and brakes. In order to slow the 240mph rocket down after a charge down the Mulsanne straight, an entirely new braking system was developed by Porsche supplier – ATE.

Flegl used an identical track and wheelbase to the outgoing 908 to create the basis for the 917’s flyweight construction. Costly materials like titanium and magnesium were used liberally to reduce weight wherever possible. Even the chassis tubing itself was narrower than most bicycle frames and housed oil lines in the pursuit of lightness.

Following on from the first forays into fibreglass construction with the gorgeous Porsche 904, Flegl created streamlined bodywork from 1.2 millimetres thick fibreglass. Even the miniscule key used to wake the 917’s gigantic engine had been drilled to save the weight of a generous pair of 1960s sideburns. A must for any serious racing driver at the time.

On the 12th of March 1969, the Porsche 917 shocked the world’s motoring press at the Geneva Motor Show. Given the project’s secrecy and Porsche’s public dismay of the new ruleset, no one saw the 917 coming. In fact, chassis 917-001 had only been completed by a weary Porsche team on the evening of the 10th of March.

Misguided new rules had supposedly intended to ban terrifyingly fast prototypes. The 917 was the rule maker’s worst nightmare. However, one car meant nothing unless another 24 examples existed.

Kurt Schild, the CSI inspector, is believed to be the first person to drive a 917. A trip around the Zuffenhausen works car park, much pointing, and some box ticking, was enough to force the CSI to begrudgingly grant the 917 homologation for competition. Game on.

Although the 917 was now eligible for competition, Porsche didn’t have the luxury of endless private testing to worm out inevitable teething troubles. The painful birth of their revolutionary racing car would take place in plain sight of rivals and press at the official Le Mans test in 1969.

Outrageous power and a streamlined shape allowed the 917 to rocket down the Mulsanne straight at over 200 miles per hour. However, such speeds were alien to Porsche and the 917’s early handling characteristics were nothing short of terrifying. A distinct lack of downforce caused the 917 to be virtually undriveable, even by the world’s best drivers.

In an era of motorsport where death and danger were ever present, Porsche struggled to convince even the bravest drivers to pilot the earliest iterations of the 917. Neither Vic Elford, Brian Redman, nor Jo Siffert could ever be characterised as timid behind the wheel. They all promptly retreated to the relative serenity of their familiar 908s after their first terrors behind the wheel of the 917.

Piech, Flegl and Mezger had concocted an unhinged machine that had to be tamed. Throughout the entirety of the 917’s three-year life, Porsche’s greatest minds methodically honed a monster into the greatest racing car of all time.

On the 14th of June 1970, Ferdinand Piech finally realised a dream which many believed to be the work of fantasy. Piloting a short tailed 917K, painted in the red and white of Porsche Salzburg, Richard Attwood and Hans Herrmann led a Porsche 1-2-3 overall at the 24 hours of Le Mans. The nearest Ferrari? 30 laps behind.

Piech may have placed the riskiest bet in Porsche’s history, but this first of nineteen outright wins at Le Mans set the Stuttgart brand on the path to the prestige it enjoys today. All thanks to the 917 and those who created this extraordinary machine.